Most people work for a wage. [1] And what is it like for us at work? We spend the best years of our lives, the brightest part of our days, doing whatever the bosses and managers tell us. Some people love their job and others hate it, but none of us are in charge. Anything can change on a whim at a moment’s notice. Even on fake “self-employment” contracts the deal is the same. We do the work and they get the profits. If we want the money to live, we have no choice but to sell a part of our time, a part of our lives, to the bosses.

And what do we spend our wages on? It doesn’t go to other wage-workers. No, it goes to businesses whose own workers make the things we buy. It goes to banks in debt and mortgages. It goes to landlords, who take a huge chunk of our wages in rent, who can evict us whenever they want, but do little for us in return. If you were to add up all the time we spend working, and compare the time people spend making things we use, you would come up short. These “missing hours” go to the landlord’s rent, the bosses’ profits, the banks’ interest payments and dividends. It’s the time people spend making the things rich people want – their posh houses, their fancy cars, their private schools, their mansions and private jets. All taken from our own labour. Their profit is our exploitation.

And stolen time is just the start. In the first place, labour time isn’t just time on the clock, but everything we do to get ready for work in the meantime: from travel, to washing clothes, to raising the next generation of workers. People call some of that “reproductive labour” and it’s all a part of our exploitation. If we didn’t do it, there wouldn’t be any workers left for them to exploit, but all the time and effort falls to us without any wages or compensation in return. Then there is politics. We do all of the work. The world economy would fall apart without us. If we stopped working the rich would be left with nothing for their money to buy. Even so, politicians mostly represent the rich and powerful. It’s broken promises for us, growth and rising profits for them. Their “austerity” closes public services, while raising politicians’ wages and expanding their police – that’s also a kind of exploitation.

When the bosses cut corners on health and safety to save money, or when the pace of work is so harsh that we get sick from stress, it’s us who end up in hospital or dead. Exploitation can be psychological. If you come home drained from talking to difficult customers and managers all day – that’s called “emotional labour”. We struggle to be present for friends and family because work has already taken it out of us. The pressure is so much that some people lash out at those they’re supposed to care for or wreck their own neighbourhoods. The burden never falls on the places posh people live, safe in suburbs and gated communities. They reap the benefits, we pay the costs.

In a hundred different ways, the people who work for a wage are exploited by rich people who do not. That’s us, that’s who we are: the working class. The class of people expected to work for a wage. Some of us might not be able to work, because of disability or because there aren’t enough jobs. But we are all part of the class that waged workers come from, and we are all treated with the same contempt by the rich. In fact, it’s part of the system – they don’t want us all in work. High unemployment makes us compete for jobs and drives down wages. Fear of life on the dole stops us from quitting. They trap benefits claimants in debt and poverty, making unemployed life a misery, in order to keep the rest of us in line.

The Owning Class

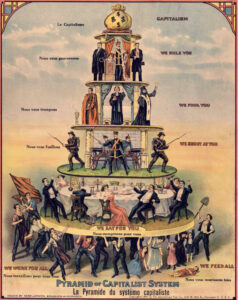

So, employed or not, all of us are working class. To be anything else – a boss, a landlord, a politician, and so on – is a choice and means standing on the backs of workers in order to get there. [2]

So, employed or not, all of us are working class. To be anything else – a boss, a landlord, a politician, and so on – is a choice and means standing on the backs of workers in order to get there. [2]

Working class people have opposite interests to these people. Every attempt to work with them ends up twisted in their favour. But who are “they”? Who are the people who exploit us and use us? “They” are the middle class and the aristocracy. The aristocracy are at the top. That includes the super rich, the kings and queens, the lords and ladies. About one third of all land in England is still owned by this small, select group of people.

Next: the middle class. “Middle class” here does not mean “middle income”, it means that class of bosses and landlords who stand in between us and the aristocrats. That “middle” includes most business owners, landlords, and members of parliament. It’s not just about wealth, it’s as much about power, prestige, and aspiration. Even if they don’t earn much they still have the power to hire and fire, they still have control over our time. A young middle class person might work in a coffee shop for a few months, but to them it’s “work experience” in preparation for owning the place, while the rest of us expect to work the rest of our lives. People from a posh background might “rough it” for a bit and pretend to be poor, with the full security of knowing their parents will set them up with a well-paid job later. It’s just an urban safari to them. That’s the difference in our mentality.

There are grey areas. Teachers used to see themselves as middle class. Now with lower wages, higher workloads, and increasing control by managers, many see themselves as workers. An artist or full-time academic might be low paid, but their influence on society and their social connections sometimes place them in the middle class too. A few “self employed” tradespeople, like independent plumbers and electricians, are genuinely free – not employed by or employing anyone else. But many are virtually employed by the banks, who take their earnings in mortgage payments and debt interest. Others are waged workers for the big construction firms in all but name.

There are grey areas. Teachers used to see themselves as middle class. Now with lower wages, higher workloads, and increasing control by managers, many see themselves as workers. An artist or full-time academic might be low paid, but their influence on society and their social connections sometimes place them in the middle class too. A few “self employed” tradespeople, like independent plumbers and electricians, are genuinely free – not employed by or employing anyone else. But many are virtually employed by the banks, who take their earnings in mortgage payments and debt interest. Others are waged workers for the big construction firms in all but name.

It’s not simple and we have to judge everyone on a case by case basis – but judging people is not the point! The point is to understand the system we live in, and why some people are more ready to fight the system than others.

The important thing is this: most people in the world are working class, exploited by an owning class who rule us for profit.

What is to be done?

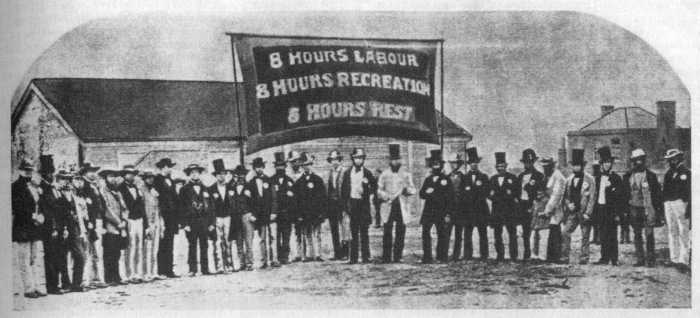

So is that it then? Are we exploited and always will be, with nothing left to do but complain or accept it? Not a chance! Exploitation is about who has the power. When we shift the balance of that power, things start to change in our favour. The way we do that is grassroots organising such as forming unions, and direct action such as going on strike. That’s how we got the 9-hour day in the UK. [3] Without the people who came before us, we’d still be working 14-hour days with nothing to show for it! That’s how we got the National Health Service and social security. When they debated it in parliament in 1943, this is what one MP had to say: [4]

Some of my hon. Friends seem to overlook one or two ultimate facts about social reform. The first is that if you do not give the people social reform, they are going to give you social revolution. {…} Let anyone consider the possibility of a series of dangerous industrial strikes following the present hostilities, and the effect that it would have on our industrial recovery…

And that was from a conservative! Fear of what our class would do to them after the war created a cross-party consensus. It still took a push to make them follow their promises. When the Labour government was dithering over housing shortages, thousands of working class families took over old army bases and empty properties. They forced the government to act. We had council housing for decades thanks to what they did, because they refused to shut up or stay quiet. [5] Whether the biggest issue is unpaid wages, unsafe conditions, or long hours – when workers get together and demand better, we win.

Those are big examples, but the actual work begins very small. Since exploitation happens in between work (selling our labour) and the community (spending our wages), that is where we start. In our own workplaces and neighbourhoods. Those are the places that we can meet other people in the same situation and figure out what to do. We’ve been told all our lives to accept the way things are, so most of us try to adapt rather than fight. To change that, we have to realise our own power. That’s why we have to start by picking an issue which is right in front of people. Something that they can win. This is called a dispute. Once one dispute is won, we stand down and start planning for the next one. We have to stop and catch our breath after each win. That’s how the 8-hour day campaign was carried out. In most cases we did not demand an 8-hour day all at once, but first 14 hours, then 10, then 9, and so on. It takes time for people to build up their confidence, so we can’t demand everything all at once. It might take years of organising around smaller issues first. But with each step we take, the next becomes a little easier.

When we look at the history of the workers’ movement we see that targeted direct action works. It’s far more effective than negotiations and lobbying and lawyers. To hell with rules the employing class make to keep us in line! The best way to improve things for our class is action organised by the workers themselves, or by the community themselves, outside the control of leaders and bureaucrats. Everything by us, for us. No matter how hard they try to make us feel small, or direct us to “the proper channels”, the fact remains that most advances have been made by our own hands, through direct action. To stand up to exploitation should not need to wait for permission from anyone. Like the working class organiser Mother Jones said:

I have never had a vote, and I have raised hell all over this country. You don’t need a vote to raise hell! You need convictions and a voice! – The Autobiography of Mother Jones

Solidarity and Workers’ Control

The reason landlords can exploit us is because they own the houses and we don’t. We may choose between renting from this landlord or that one, but as tenants we can’t opt out of renting altogether. The most ruthless landlords make more money than the rest and then use that to buy more houses. They take more and more until they are running most everything, leaving us no escape – stuck in flats and houses that fall apart around us. If we complain, they send in the bailiffs and eviction notices.

The reason landlords can exploit us is because they own the houses and we don’t. We may choose between renting from this landlord or that one, but as tenants we can’t opt out of renting altogether. The most ruthless landlords make more money than the rest and then use that to buy more houses. They take more and more until they are running most everything, leaving us no escape – stuck in flats and houses that fall apart around us. If we complain, they send in the bailiffs and eviction notices.

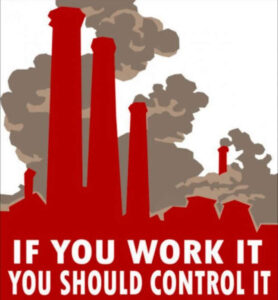

The reason employers can exploit us is because they have the money to pay our wages and because they own the “means of production” – the factories and the fields and the machines and the tools (and also the social connections and networks of suppliers). As we don’t have any of that, definitely not enough to compete with them, the only way to make a living is to sell them the one resource we have: our time. The meanest of the lot buy out their competitors, and any boss who tries to be “nice” is run out of the market.

The PROPERTY system lies underneath class exploitation. It keeps the owning class in control, and us dependent on them for wages. If we try to fight it alone, they call in police and bailiffs to beat us down and kick us out. The class war is really a war for workers’ control of the means of production and the means of life – to put it in our hands rather than theirs.

All of our resistance involves taking back control from the owners, even if it’s only for a short time. A strike shows their property is useless without workers to run it. Action against job losses challenges their power to hire and fire. Demanding repairs from a landlord challenges their right to do what they want with the property they own.

We fight the class war because with each step forwards, with every advance, we make things better for ourselves. Every bit of power we can claw back from the owners means better living conditions and prosperity for our class. Not just in an individual workplace or neighbourhood, but everywhere. When they see what some of us are capable of it gets easier for all of us to make demands. That’s why we have traditions like “never cross a picket line”.

All of us have a stake in every fight. If they make an example of any one of us, everyone else will be intimidated into silence. That’s why solidarity is so important. We can’t just limit it to one workplace or one industry or even one country – solidarity is international. Otherwise, if we let them play our class against each other competing for lower and lower wages, they will make mincemeat of us all.

Solidarity isn’t just about us and them. It changes how we are with each other. Fighting together for something better, rather than fighting for the scraps amongst ourselves, undermines all the walls the owning class have built between us. When we truly support each other in solidarity there is nothing they can do to stop us. That’s what this is all about. This is what “organising” really means: building relationships of solidarity with each other. The rest of this series is about how to make that happen. What kind of organisations we make and how to direct our action. For all the talk of strategy and fighting and so on, it’s important to remember: at heart what we are trying to do is to build relationships of solidarity. That’s how we will beat the owning class.

The next article in this series, to be released next week, will look at the tactics working class people have used to win disputes…

Footnotes:

[1] – that is, of around 6 billion adults worldwide, about 3.3 billion are currently in employment. For children, the same proportion can be expected to work in their lifetime. The next biggest group after waged workers in subsistence farmers, who number about 2 billion (George Rapsomankis 2015, The economic lives of smallholder farmers)

[2] – globally there is also one more class – the peasantry, people who work the land directly to grow what they need. They might work common land, or own some, or rent it from a landlord. While this class is bitterly exploited elsewhere, they no longer really exist in the UK. They were all forced off the land in order to create the working class of today. For more information on the situation of peasants, please see the Via Campesina, who represent over 200 million people worldwide – viacampesina.org

[3] – Tom Brown tells a part of this story in Fighting for the Nine Hour Day libcom.org/library/fighting-nine-hour-day-tom-brown. See also The North-East Engineers’ Strikes of 1871, by E. Allen, N. McCord, J.F. Clarke, D.J. Rowe for a more detailed account of the movement and the importance of direct action within in

[4] – hansard.parliament.uk/Commons/1943-02-17/debates/387e1885-4fa4-480c-8815-2b83328272bf/SocialInsuranceAndAlliedServices?highlight=revolution%20reform#contribution-c7e7ce16-7754-422d-b2b2-b0ad6fd34582

[5] – See the documentary Their World This Time by Platform Films – youtu.be/d3-Du41_L8k